FALL RIVER: It took Phonse Jessome getting a formal diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in 2007 for him to take it seriously.

“I was told I could never work as a reporter again,” said Jessome. “I ignored that, and continued working. I then realized I can’t keep working until 2027, which is my retirement day, at this rate because the PTSD was getting worse and worse.

“The likelihood of my continuing as a reporter just wasn’t good.”

The 54-year-old thinks his days as a journalist are behind him—something, as hard as it is, he has come to terms with, and a decision his family is happy he has made.

“I know I can do it, but the problem is the doctors say don’t,” he said. “In fairness to my family, I did it much longer than I should have. I don’t want to put them through that again.

“I miss it everyday. I’m kind of young to be finished, especially something I started when I was 17-years-old. But I have to be a grown up and accept I can’t play the game anymore. I’ve got a new passion I hope in writing this series.”

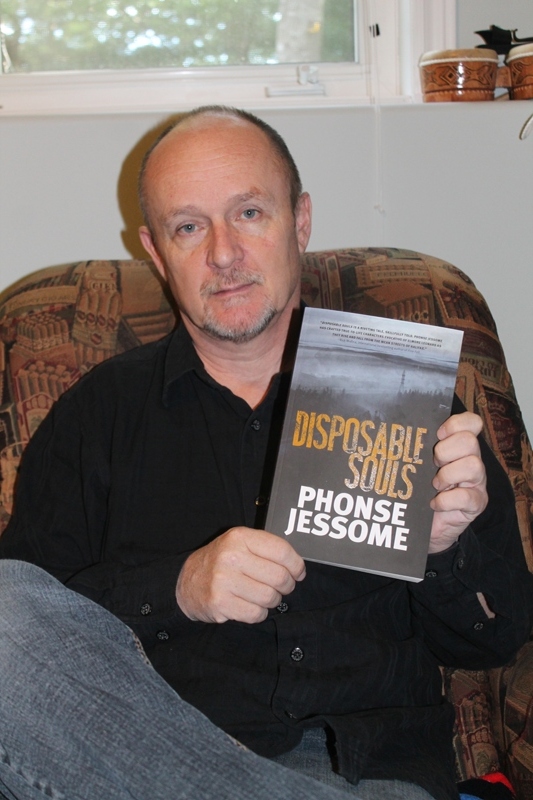

He has just recently released a fiction novel through Nimbus Publishing called Disposable Souls. The main character, a police detective named Cam Neville is inflicted with PTSD.

Jessome detailed the news he got from his doctor—and what led him to finally say enough was enough, and he left the CBC.

“It was a day after a session I had with the doctor and he had explicitly told me I could not do this any more,” he said. “I refused to accept it.

“The next morning I was driving down to the South Shore at 3:30 a.m. and I got to watch them pull a frozen body out of the ocean. That was my job. Breaking news. Breaking news isn’t a job about the county fair. Breaking news is about what’s happening that’s bad. That’s where I went. That’s where I did my best.”

That day finally came after covering a story at Halifax Stanfield International Airport.

“It was in the Spring of 2014. I had an exclusive. There was a near disaster there during a blizzard. A plane tried three times to get in and it was bad,” he said. “The people were wrapped in blankets. I was interviewing them and they were crying. Some were sick.

“It was a highly emotional story, but they didn’t crash. It was a good news story. If they had of gone down, by the grace of God I would have been—and you would have too—been there covering a plane crash. Something went wrong.”

He said he did his normal routine—filed his story for the web; did his radio hits; and did the interviews on camera for the TV piece.

“I sat down at 8:30 a.m. to regroup when the radio rush was over and think of what I needed to finish my TV piece,” he recalled. “I froze. I couldn’t pick up the camera. I remember looking at it on the floor. I couldn’t pick it up.

“I ended up taking it back downtown and asking a cameraman to go out and finish shooting the b-roll for me. I did cut the story.”

Jessome hosted Information Morning the next morning.

“I went from there to the doctor, and they hospitalized me,” he said. “I was dehydrated, sleep deprived, my Crohn’s disease was acting up. They diagnosed me as having severe CPTSD (Complex PTSD), which is a level deeper. Because I had continually exposed myself I had made the disorder worse. At that point it was all on paper, and I couldn’t go back to work without the signatures of the doctors. They won’t sign. But that was the end of the line.

“I’m a little healthier now than I was then.”

Jessome said one of his hopes is that PTSD may get a little more awareness as a result of the book.

“I want to make the conversation about PTSD as much as I do about the book,” he said. “I want to show people you can function with PTSD as I did for a very long time at a very high level.”

He said he may have needed the last two years to get himself healthy enough to be able to do what writers do—promote their novels.

“I’m healthier now than what I was two years ago,” he said. “I’m petrified of going out and doing readings, and doing the launch (in Digby at the Wharf Rat Rally), but that’s part of it.”

For the past two years, Jessome has only stepped outside his Capilano Estates home to go see doctors.

“I’ve got to test myself as I’ve been hiding in here,” he said. “It’s time for me to get myself back out in the world and see if I can function.”

phealey@enfieldweeklypress.com